“The world,” Salman Rushdie wrote in The Satanic Verses, “is the place we prove real by dying in it.” Happily, defiantly, the author, 75 and among the greatest of all living make-believers, is not ready just yet to test that theory. Reading his interview with David Remnick in the New Yorker last week, the first he has given since he was attacked on stage last August – stabbed 15 times in the face and neck and chest and hands – was to be reminded of some of the darker ironies of his existence.

In the years since he came out of hiding after the 1989 fatwa and moved to New York, Rushdie had begun, he noted, to evoke frustration, even ridicule for trying to live normally, as if he’d been exaggerating the threat all along. “People didn’t like it,” he told Remnick, “because I should have died… Not only did I live, but I tried to live well.”

“Now,” he suggested, “that I have almost died, everybody loves me.” The trauma and the consequences of the attack are no doubt a struggle for him. He has lost the sight in one eye and is trying to regain feeling in his hand. Rushdie, fortunately, has something of an inbuilt solution to all that, the same one that has served him so well for the 33 years since his life became a news item: he plans to have the last word by writing about it. Storyteller, not story.

A couple of weeks ago, Cate Blanchett took Margot Robbie to task on Graham Norton’s sofa for her professed love of heavy metal music: “Does anyone really like that?”. Blanchett, with a hint of her imperious recent performance as unhinged classical composer in the film Tár, inquired if Robbie “also liked monster trucks?”. Twitter, as they say, lit up with posts from diehard metalheads. “Naff off luv,” one user told the “condescending” Oscar winner. Another added: “Yes Cate, people like heavy metal. I’m sorry we don’t all listen to impenetrable Greek tone showers or Soviet show tunes from the 1930s.”

With perfect timing, last week, Birmingham Royal Ballet’s director, Carlos Acosta, announced a show that might bridge that particular culture gap: “Black Sabbath – The Ballet”. This homage to the second city’s greatest musical export will be staged at the Hippodrome, only a mile up the road from where Sabbath’s guitarist, Tommy Iommi, lost the tips of his fingers on his last shift in a sheet metal factory and reinvented the sound of rock’n’roll. Perhaps Blanchett could be persuaded to attend the opening night in September and hear what she has been missing.

Hedging our bets

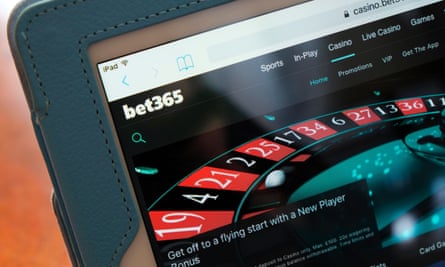

One of the lasting legacies of New Labour was, in effect, to put a roulette wheel in every living room. The liberalisation of the gaming laws in 2005 came in advance of the great explosion of smartphone betting – and the related harm and addiction. The Tories’ 2019 manifesto promised a white paper that reformed those laws, particularly the way that adverts were targeted at young and vulnerable people (eight premiership clubs still carry betting ads on their shirts). That white paper has been delayed through five ministers of culture, media and sport. In the meantime, the gambling companies continue to count their winnings – Denise Coates, boss of Bet365, pocketed £260m last year. Last week in the US a bill was put forward to outlaw “predatory” gambling advertising in line with the vast majority of countries. Our own government, unforgivably, characteristically, continues to hedge its bets.